Blogging History: China’s Islamic Christopher Columbus

Decades before Christopher Columbus was even born, 18 years before Europeans began their “Age of Discovery,” an Admiral from the Chinese Empire sailed west, explored unknown lands, visited with strange “barbarian” peoples, and projected Imperial might as far away as Africa, covering more than 50,000 kilometers in his 7 epic voyages. I saw the story of the legendary navigator Zheng He mentioned in passing on History Channel’s Engineering an Empire and I was so fascinated, I had to research him so I could highlight him on my blog.

Zheng He was born Mǎ Sānbǎo in China’s southwestern frontier Yunnan province, in 1371. He was of the Hui ethic group, which is similar to the predominant Han Chinese, except the Hui have been practicing Muslims since early on in Islam’s spread. Mǎ Sānbǎo’s father and grandfather had both been on the hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca (no small task).

Young Sānbǎo grew up during a time of great turmoil in the Chinese Empire. The majority Han Chinese got tired of being oppressed by the Mongolian-led Yuan Dynasty (dynasties never learn) and a mass peasant revolt overthrew the regime and forced the Mongols back into the steppe. In 1368, peasant leader Tai Zhū established the Ming Dynasty, ascended to the throne as the Hongwu Emperor, and enacted highly successful reforms, such as redistributing land to the peasants, which vastly increased China’s stability and power.

The Emperor proclaimed his motto “Exiling the Mongols and Restoring China,” and when Mǎ Sānbǎo was 11 years old, the Ming Imperial army overran his home province with 250,000 troops to take down a Mongol holdout. The army captured Sānbǎo in the process and castrated him. He was brought to the Imperial court as a gift to the Emperor, where being a eunuch was required to work in the royal household (to ensure that the Emperor’s aides couldn’t spawn a competing dynasty, and perhaps thinking eunuchs wouldn’t touch his hottest courtesan women).

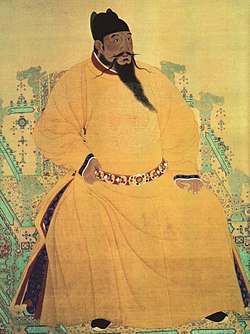

Mǎ Sānbǎo became a court servant, and after a dynastic struggle and civil war in the wake of Hongwu’s death worked itself out and the Yong-le Emperor took the throne, Sānbǎo became the new emperor’s closest adviser. In honor of his service in the civil war, Yong-le called him Zheng He, and this was his new Imperial name (alternately translated into English as Cheng Ho).

Yong-le directed a stunning expansion of China on a scale not seen again until the 20th century. He imposed a sort of Pax Sinica on the whole region (similar to Pax Mongolica). Yong-le’s reign was one of secure dominance over all of China and no real threats to the Empire. Relative tranquility prevailed (though not if you were living in one of the several neighboring states that Yong-le violently subjugated). In addition, Yong-le forced virtually every kingdom in East Asia, even as far away as Thailand and the Philippines, to become tributaries (i.e. extorted tribute from them).

The Yong-le Emperor marked a peak in Chinese confidence. He sought to advertise China’s cultural superiority to the rest of the known world and to this end, he distributed 10,000 copies of the Biographies of Exemplary Women to various non-Chinese countries for their moral instruction, and he oversaw the compilation of the vast Yong-le Encyclopedia, documenting the Yong-le era and incorporating eight thousand texts from ancient times.

Yong-le also dominated maritime trade. This is where Zheng He comes in.

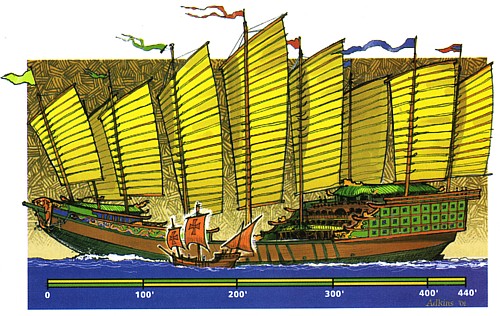

Zheng He captained seven naval expeditions to project Imperial power, protect and extend Chinese trade, and possibly vassalize far-away peoples. He assembled a huge naval fleet–317 ships holding almost 28,000 armed troops for his first voyage. By comparison, the U.S. Navy in 2007 has only 277 ships on active duty. .

Imagine if you were an early 14th century Indian or Arab, and saw 317 ships bearing down on your harbor! This was meant to impress (and intimidate) foreign peoples into paying China tribute.

Zheng He led his fleet with 62 mammoth, nine-masted “treasure ships.” They are described as so massive (400 ft long and 170 ft wide) many experts dismiss them as impossibly large, because early modern ships of comparable size were unwieldy and usually sank. However, history is full of unexplained technology. We have no idea how the Romans accurately engineered something as large and complex as the Colosseum without Computer Aided Drafting, and we don’t know how the Byzantine flamethrower ships that saved Constantinople worked (they are neigh-impossible to duplicate even with modern welding methods). So I wouldn’t dismiss Zheng He’s treasure ships as impossible.

China hired a Swedish shipwright to build a replica of a Zheng He treasure ship to serve as a symbol for the 2008 Beijing Olympics (story). At almost 250 ft long, it will be the largest wooden ship ever recorded, and they hope to retrace Zheng He’s voyages with it.

But where did Zheng He (pronounced “Zung Ha”) go with his legendary fleet? And what did he do when he got there? Well, on his seven voyages he went up and down Indonesia, visited India, Persia, Arabia and Africa. The purpose was to make “first contact” with strange new peoples (like the S

tarship Enterprise) but also awe them with China’s power, give gifts of their finest silk and porcelain (showing superiority) and in exchange, extract tribute. Zheng He brought back gifts of African zebras and giraffes for the Imperial zoo.

In at least one instance, Zheng He’s missions included military confrontation. On several occasions, he ruthlessly took down pirate networks that had been plaguing Chinese shipping. Each of the seven voyages included stops in Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka), an important gateway for Chinese trade routes. Evidently, the ruler of Ceylon, King Alagonakkara, had been threatening his neighbors, and pirating Chinese traders. Zheng He came to deliver a message from the Yong-le Emperor: “stop it. respect my authoritaah.” King Alagonakkara refused, and sent troops to attack and loot the Chinese fleet. Zheng He ordered his soldiers to attack the city to draw the enemies away from the ships. He ended up capturing King Alagonakkara and brought him back to Nanjing to apologize to the Emperor.

Some speculate that tales of Zheng, a Muslim explorer from the East who made seven voyages, and his name Sānbǎo, inspired the tales of Sinbad the Sailor, but there’s nothing concrete to back this up.

Zheng He made it all the way down to Kenya (they found ancient Chinese artifacts there) and there is some evidence he went beyond the tip of Africa and into the Atlantic Ocean. Zheng himself wrote of his travels:

We have traversed more than 100,000 li (50,000 kilometers) of immense water spaces and have beheld in the ocean huge waves like mountains rising in the sky, and we have set eyes on barbarian regions far away hidden in a blue transparency of light vapors, while our sails, loftily unfurled like clouds day and night, continued their course [as rapidly] as a star, traversing those savage waves as if we were treading a public thoroughfare…

— (Tablet erected by Zheng He, Changle, Fujian, 1432)

Zheng He left a monument on Sri Lanka too, honoring Islam as well as the local deities (Vishnu and Buddha). He also erected a monument in India. One quack author thinks Zheng’s crew left structures in the Americas.

Did Zheng He “discover” America?

No, it’s crap. There’s no evidence to support that, but former British submarine captain Gavin Menzies (who has no historical training) has made a killing with his discredited 1421 hypothesis, and is selling books, maps and TV specials convincing people that Zheng He found the Americas before Columbus and circumnavigated the globe before Magellan. Menzies bases his theory on wild speculation, and an 18th century Chinese world map showing America that he (falsely) claims was made in the 1400s. He also alleges that old structures such as the Newport Tower were built by Zheng He (rubbish) and that Native Americans are actually children of Zheng’s crew (laughable). This is the perfect example of historical hucksterism.

Still, it revived interest in Zheng He, so I guess that’s good.

If you get the History International Channel, check out Zheng He: The True Discoverer of America? which airs tonight (Monday) at 8pm ET / 7pm CT.

Part of the reason so much speculation surrounds Zheng He’s later voyages is the records of them were destroyed. After the Yong-le Emperor died in 1424, Zheng He lost his influence. Conservative Confucians assumed control of the Imperial court, and seeking “inner perfection” first, implemented very isolationist policies. Also, the new emperor needed to devote considerable resources to beating back Mongol hordes in the north and expanding the Great Wall of China to keep them out, and Zheng He’s lavish missions, which were mostly for prestige (and unlike European explorations were not self-funding with loot) were no longer financially viable. The new emperor burned Zheng He’s glorious ships, destroyed a lot of his documents, and banned maritime trade. Though the subsequent emperor lifted the ban and let Zheng He voyage again, a lot was lost.

Can you imagine how history may have been different if China had continued as a maritime superpower?

If China had continued on the path of Zheng He, much more of the world may be culturally like Indonesia now. Zheng He made a significant impact on Indonesia. His voyages there are well documented, and he left Ming-style architecture behind, as well as lots of Chinese people. He relocated a lot of Chinese Muslims to Indonesia and Malay. Indonesia is the most populous majority-Muslim state on Earth today, in no small part due to Zheng He and his crew promulgating the Islamic faith there. He was buried at sea when he died during a voyage in India in 1433, but has an Islamic tomb in Nanjing. “Allahu Akbar” is inscribed in Arabic above the door.

The People’s Republic of China recently is using Zheng He as a role model to integrate its tens of millions of Muslims into Chinese culture.

They are also using him as a symbol of a peaceful rise as a superpower.

Expect to hear a lot more about Zheng He, and Pax Sinica, very soon, especially surrounding the Olympics.

Nick