Patrick A from PunkTorah asked me to comment on parsha Emor, and here’s what I came up with.

Everyone please turn to Leviticus 21, kthx. In this week’s parsha, Emor, Moshe Rabbeinu (Moses) tells us about some of the laws regulating kohanim (Temple priests).

After the admonition for kohanim to not have contact with corpses, parsha (portion) Emor goes on to list the various deformities and disabilities that would disqualify a kohen from performing his Temple duties. They include: blindness, mobility impairment, sunken nose, unibrow, broken or twisted limb, one limb disproportionate to the other, sores, and, of course, crushed testicles. If the Temple was excluding disabled priests, does that mean Judaism is discriminatory and ablist?

Josh over at parshablog says one possibility is that this is a concession to the prevailing cultural attitudes of the time. DovBear suggests that this is just one of several “rules and requirements and presumptions that no longer fit anyone’s idea of morality” in Torah.

I don’t fully agree with either of these opinions. I think there’s nothing we can’t learn from, especially words of Torah (nothing is not relevant, and if you’re not able to find something to learn from in a chapter, you’re not looking hard enough).

What can we learn from this? Well, to me, ablism means blocking people with disabilities from doing things we can do, assuming we have nothing to contribute, and stifling our potential. It doesn’t mean I get an equal shot of playing shortstop for the Yankees. Maybe a disabled kohen can’t drag a bull up the ramp to the sacrificial altar. And we have to remember that Torah was recorded during a time where G-d was smiting people as an example that even minor infractions should not be committed with the Temple service. This was a lot more important than a Yankee game, and if you were reckless in the Temple, G-d would be reckless with us (i.e. smiting). In Torah, every tribe and every person has a role they’re born for, and that’s one lesson we can take away. And in this life of confusion, chaos and darkness, one who finds their purpose, their meaning, is fortunate indeed.

I’m not offended by the stringent requirements for Temple services. Disabled kohanim were only barred from leading Temple rituals. They were never stripped of their title, and were still allowed to eat from the holiest of sacrifices (they got all the benefits of their role). Some were even allowed to perform the priestly blessing (source).

And unlike illegitimate kohanim, disabled kohanim continued to keep all the benefits, and all the priestly laws. To suggest a physical defect is a spiritual defect (as this commenter did) is ablist and false.

The fact that disabled kohanim stay kohanim, and can’t be expelled, is fascinating to me, and I think we should learn from it.

Also in Leviticus, those with skin disease never have to pay for their affliction (free health care). The Torah makes sure that anyone in need is looked after and cared for. Kohanim were responsible for properly caring for and overseeing infection control for the community.

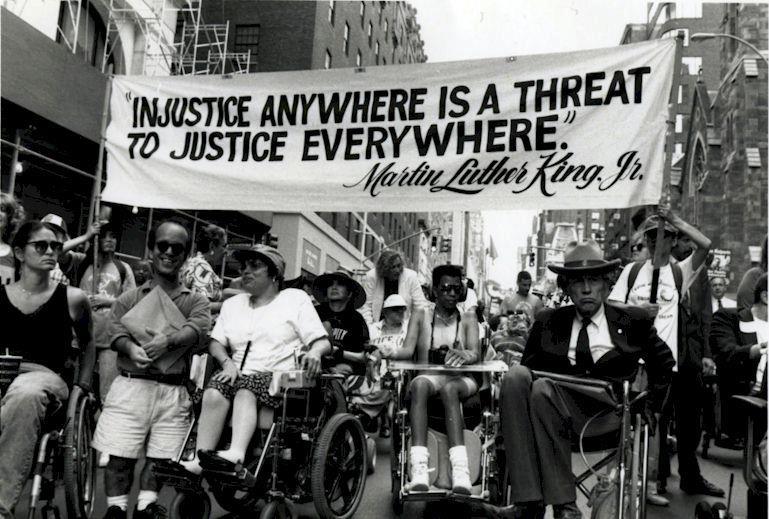

People with disabilities are never excluded or discriminated against in the Torah. Isaac‘s blindness certainly never diminished his authority as a Patriarch and leader.

I see Torah as proposing a semi-Utopian system, where everyone matters, everyone has a role, everyone has a portion, not the cruel dystopia many paint it as.

Nick

Here is the PunkTorah commentary on this blog. And check out the video:

And to see all the PunkTorah videos, go to the PunkTorah YouTube Channel.