An Independence Day post (belated) – bloggery for the Founders

We would do well to mark the 4th not with the flag-waving militarism and “fighting for freedom” boo-yahs that typify so many public Independence Day events, and focus on the thing that Independence Day was really commemorating: the Declaration of Independence (adopted prior to large-scale war), our separation and unique vision for our republic. It should be a day of reading the Declaration of Independence and Constitution first and foremost, and yes, as John Adams wrote, “It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other…”

And in addition to a day of remembering the actual founding documents and principles, which include freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures of your files, we should have a day of loudly reading, painting, sequential art explainer-drawing, studying, and debating the ideas of the founding brothers and sisters (their actual ideas, which are really diverse and disagree with each other). We can glean relevant lessons for today from all our founding people.

Today I’m talking about George Washington’s ideas. Exalted as the first General of the first-ever separate American army and victor of the War for Independence, his actual words and ideas get lost.

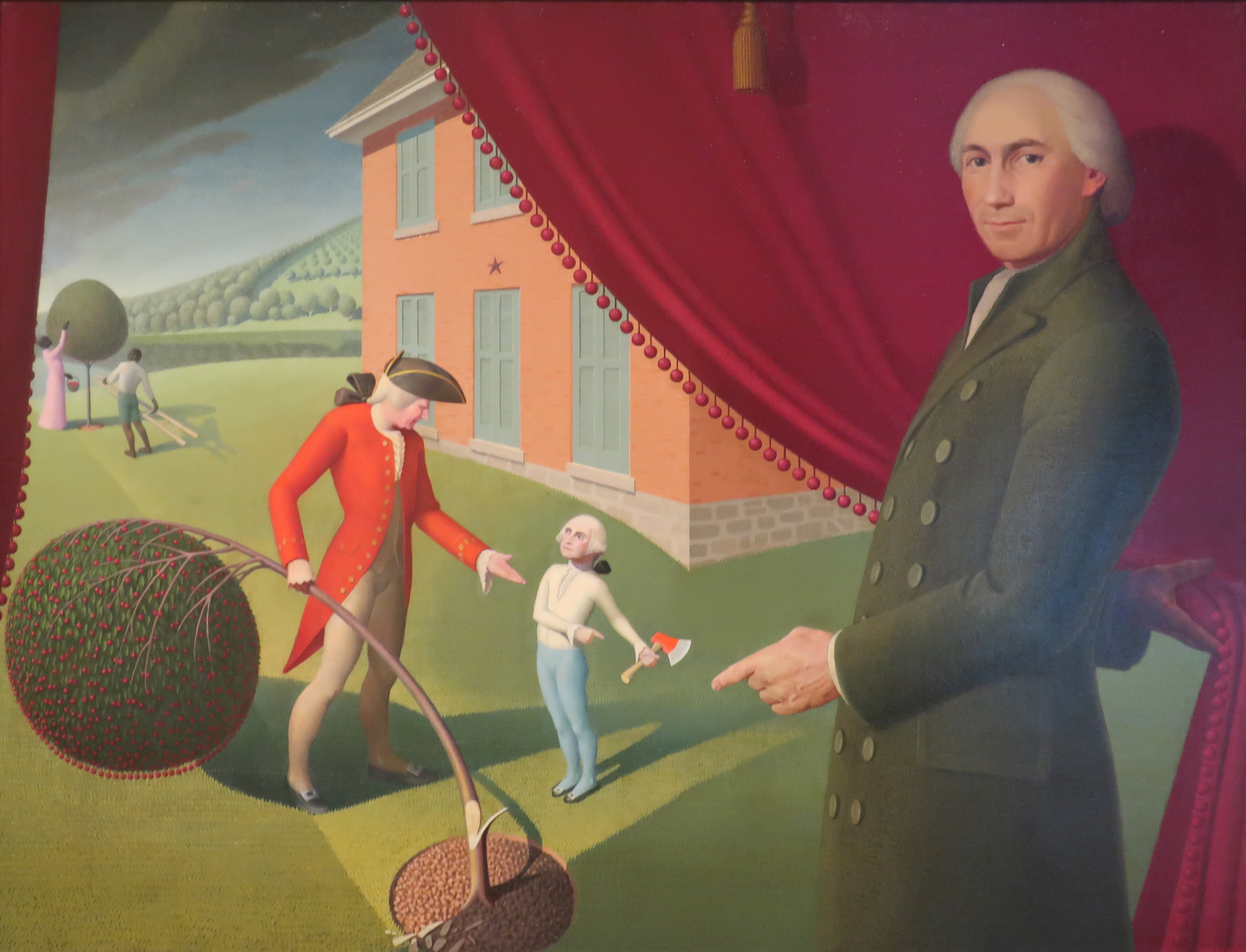

John Adams objected to this oversimplified exaltation of the revolutionary generation more than anyone else. Adams was always writing letters lamenting the editing out of the Revolution’s complexities, that the Revolution was a process not an event and its processes were as diverse as the 13 colonies that fought, and that the gruesome War for Independence was waged at great cost of life and limb and nothing to boo-yah about! He hated

the prospect of the Independence struggle being dumbed down so badly that kids think “Washington chopped down a cherry tree,” the redcoats ran, and everything was copacetic. In the years prior to John Adams’ death, the leading figures of the revolutionary generation were increasingly remembered in low-information hagiographies, a trend that was yet to peak. Throughout the 1800s, the founding fathers were so ridiculized and mythologized, you end up with craziness like Constantino Brumidi’s 1865 fresco The Apotheosis of Washington on the oculus of the capitol dome ceiling to this day, depicting Washington ascending to the heavens and becoming a god, AKA apotheosis,

surrounded by figures from classical mythology, the goddess Victoria (draped in green, using a horn) to his left and the goddess Liberty to his right (seriously).

But George Washington wasn’t a deity like Zeus. George Washington was a person, and as much as he preferred to stay atop his white horse looking majestic and being “above the fray,” he was often forced into the fray. He had opinions, and if you think of late 18th century American politics as a spectrum—Jeffersonians with states’ rights positions and a vision of the United States as an almost E.U.-like confederation with a tiny low-tax federal gov’t that’s big enough to do foreign policy and raise armies (kinda) in the event of national emergencies but little else on one end of the spectrum, and the Hamiltonians who advocated a strong national gov’t with united goals, federally funded “internal improvements,” more spending for a federal military, and the taxes to pay for such a robust federal gov’t. on the other end of the spectrum—Washington was more of a Hamiltonian, through this vastly oversimplifies Washington. George Washington adopted Alexander Hamilton as a political right-hand-man of sorts, and though that relationship got very fraught and cranky and “good day to YOU, sir!” even breaking up sometimes—read Ron Chernow’s excellent biography Alexander Hamilton for the details—Hamilton’s influence on the old dude was unmistakable, especially when it comes to things like Washington’s famous Farewell Address, where Hamilton’s ideas are particularly prominent.

But Hamilton and Washington were very different men. Being roughly a generation older, and a pious Virginia landowner, George Washington always saw the world through a distinctly “landed Virginia gentry”-type of lens, and definitely held a vision for the United States of a republic of white yeoman farmers independent of corrupt cities, similar to the vision of fellow Virginia bros Jefferson and Madison, though better on the question of slavery. Washington was definitely way better than Jefferson at freeing the slaves on his estate; Jefferson only freed five slaves in his will, all males of the Hemings family. two of whom have DNA-tested positive as his sons.

With George Washington, after his presidency and time teamed with Hamilton, you get a man applying the federal “internal improvements” concept, a robust program of road-building and canal-ing, to his goal of a nation of republican landowners. You get Washington: rural technocrat. This is super interesting in light of today’s infrastructure problems, rural America being in its death throes and so on. But there isn’t much written about “Washington the technocrat,” aside from chapter five of Paul Johnson’s George Washington: The Founding Father, available as a stand-alone book, or as part of the Eminent Lives presidents collection as an ebook or audio conglomeration.

An excerpt:

Back in Mount Vernon, Washington, now fifty-two, took stock of his personal state… Not for the first time he reflected that America’s first problem was the tyranny of distance. It was vast, and growing each year, and communications were not keeping up. … He saw America increasingly in unitary terms and this vision was strengthened by further travels… His diaries show what chiefly interested him: the impact of distance on the economy, social life, and opportunity. Any steps to speed up travel were central to the country’s future. He noted that stagecoaches ran three times a week from Norfolk, Virginia, up to Portsmouth, New Hampshire. But just to get from Richmond to Boston by stage might take twelve days. There was one good wagon road into the interior, but south of Virginia, roads, stages, and tracks were so bad that people preferred to travel by sea, a sure sign of a primitive transport economy.

…Washington was the pioneer. He realized early that the tyranny of distance could be reduced by intelligent use of her tremendous rivers, having canoed some of the fiercest himself. As early as 1769 he tried to promote the use of lock canals to improve natural waterways like the Potomac and Ohio. The canal (linked to improved post roads) was the dynamic of the revolution in transport of the eighteenth century, just as steam was for the nineteenth, and the internal combustion engine, in cars and aircraft, was for the twentieth. Washington’s diaries show that as soon as the war was over he turned again and again to canals. In September 1784 he traveled across the Alleghenies partly to inspect his western lands but also to plan canal routes (and roads) to link Ohio tributaries to the Potomac. …In May he became president of the Potomac Navigation Company, empowered with a joint charter from Maryland and Virginia to improve roads and build canals throughout the area. As always, Washington pushed for the rapid development of the area, emphasizing that improved transport to the whole Ohio valley was the surest way to bind the settlements there to the states, and encourage new ones.

It’s not much of a stretch to imagine Washington enthusiastically advocating and

planning high-speed rail lines today if his head were preserved Futurama-style, or planning for freight trains for the underserved Southern states during the 19th century rail revolution he didn’t live to see. He was also big on Ag innovations and new technology to improve livelihoods for American farmers.

Most of Virginia’s representatives today are skittish at best about any sort of centralized infrastructure planning, but George Washington wasn’t. When reading the aforementioned chapter, it comes through clearly: Washington expected people to get behind things like the Potomac Plan. Building infrastructure so your country can function is simply leadership, and he was disgusted by the federal Congress’ inability to deal with the desperate need for transportation infrastructure. The system now is even more unable to do things; we’ve got corruption in Congress and federal agencies rivaling only the capital’s “Gilded Age” machinations.

But I think we would do well to internalize ol’ GW’s ideas about internal improvements.

Nick