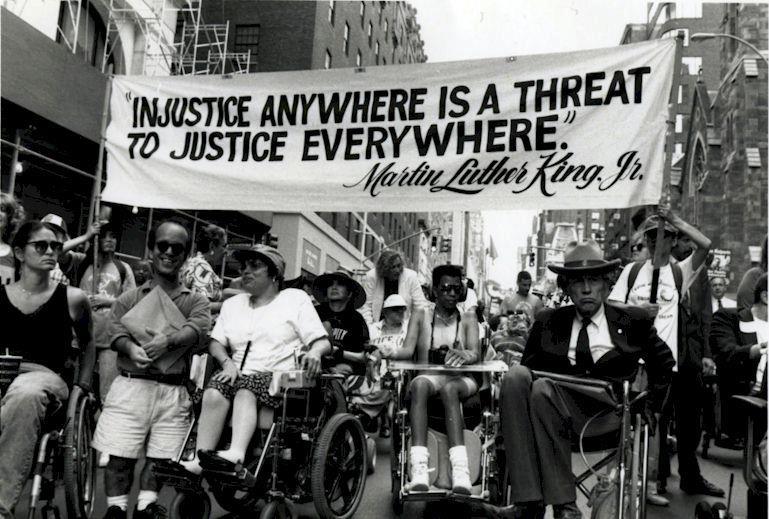

I had originally intended to write this for Blogging Against Disablism Day, BADD, 2012. Obviously I’m WAY late for that, over two days after the deadline. But since I’ve participated in BADD in the past, I said hey, why not?! Maybe BADD readers will still find this post, and may, along with other audiences, find “The Path of the Disabled Man” of interest. I’ve never written about gender before. This is an attempt to convey something of the disabled male’s lived experience, and I hope it works.

The Storms Within

People forget, but though humans DO have a spiritual core, they’re coming from tens of thousands of years in the cave as well. Certain things are in-born, hard-wired in the base end of the forebrain, or reptilian brain or whatever you may call it; right next to things like fight or flight, territoriality, hunger and other instincts in the lower brain are our sexuality and some fundamental guides of human attractiveness, passed straight down from the caveman/cavewoman experience.

Those looking for a good cavewoman to pair with, knowing all too well that the pairing would need to produce like eight kids within a decade before the end of your life expectancy at age 30 to have maybe two of your offspring survive in a bleak era of horrendous infant, child and adult mortality—something that would continue to be a huge factor in the everyday lives of humans until the emergence of modern medicine in the 20th century, would automatically look for a cavewoman with a healthy look like she could carry eight babies, full breasts that look like they could feed two babies at once, nice skin signaling health, and a good-looking symmetrical face (a subconscious indicator of good genes in all humans). This is hard-wired in the brain as guideposts pointing toward female attractiveness, as shown by its prevalence today across cultures on all six inhabited continents. A deep, bedrock thing in the mind; though largely subconscious, it remains ubiquitous.

Those looking for a quality caveman to pair with would automatically seek out the strongest, most battle capable male, who could kill wildebeests and rival tribesmen so the she and the offspring can survive (ironically, with acts of violence, including literally beating an adversary’s brains out, an act of protection and love for the woman). The images of males that women are interested in tend to feature images of strong men, not naked as men like to look at women, but in clothes that convey a status or role as providers and/or protectors, e.g. men in uniform, firemen calendars, etc. What’s attractive in the human male (for most) is more subtle and complicated, but it’s no less hard-wired.

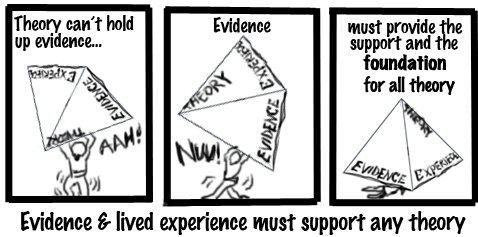

So where does that leave men with permanent disabilities? I’m a guy who’s continually trying to find my way as man, and be a good man alongside severe disabilities in the mix, things like needing a ventilator and intact breathing tubes an inseparable part of my lived experience day-in and day-out and a real barrier. So I’ll speak to that—not meaning to say the path of the disabled male—I include the gay male here, similar challenges—is harder than other paths. And no denying it can be super difficult for women with disabilities given the ableist society we live in, and ambitions today rightfully dwarf the cavewoman’s (and not meaning to discount the struggles of those on transgender or gender queer paths either, which, in my view, is no less hard-wired a position than mine, as evidenced by the cavemen AND the animal kingdom). Of course, regardless of gender, everybody wants the same basic foundational things, to feel safe, wanted, needed, like they matter. This is just “write what you know,” about the lived experience of gender, not “gender theory,” and not intending to say the path of the disabled male is harder, but it is different, very different.

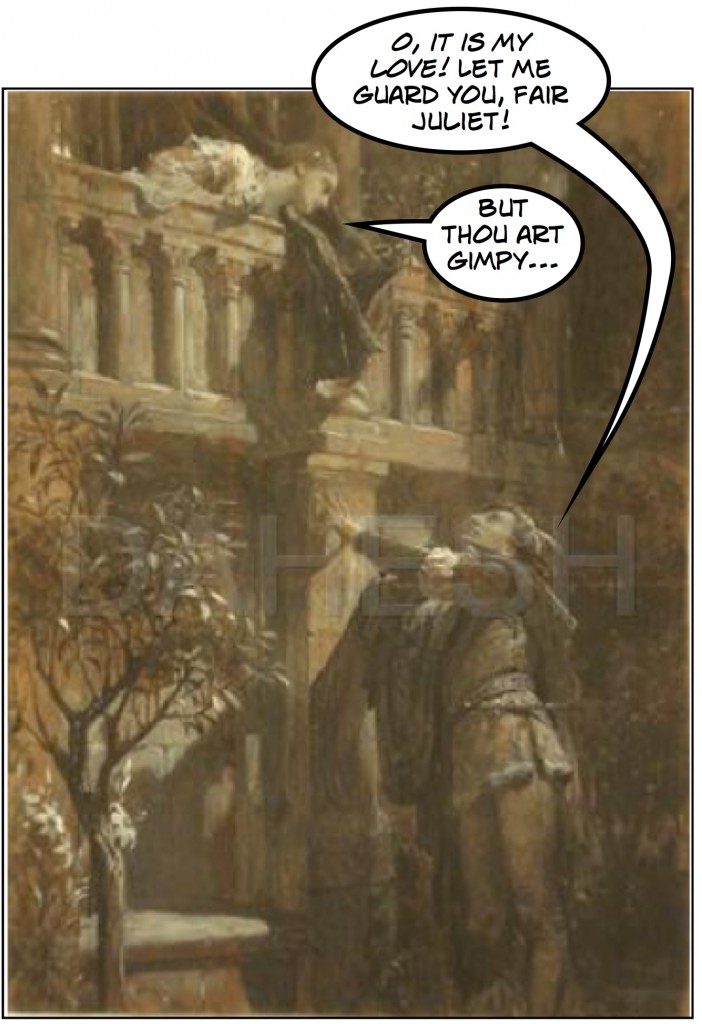

Women with disabilities, predominately, can still have the fundamental elements of female attractiveness society expects, there is obvious beauty abundant here (I admit, I’m biased in favor of disabled women) while men with disabilities have an incredibly difficult time being providers and protectors.  It’s an uphill battle feeling valuable in any sort of male gender role a disabled guy has attempted to carve out. Men can have physical attractiveness too, no question, we can rock the good-looking symmetrical face with the best of ’em; but while that may open doors, it won’t take you far beyond that because everybody tends to, consciously or unconsciously, want men to be protectors and providers, and frankly so do I. I don’t think women who want that from men are “superficial,” I see it as a legitimate, totally valid need. And focusing on what the man offers and actually does is, truly, less “superficial” than how men size up women, which, until a guy matures, will heavily tilt toward the body. Anyhow, to be useful in that way, protecting, providing, being a doer, taking specific actions, physical or not, that matter to someone, is a core thing in the male psyche (granted, “writing what I know” here does involve projecting forth my own feelings and perspective, but I do think a lot of this is universal across men).

It’s an uphill battle feeling valuable in any sort of male gender role a disabled guy has attempted to carve out. Men can have physical attractiveness too, no question, we can rock the good-looking symmetrical face with the best of ’em; but while that may open doors, it won’t take you far beyond that because everybody tends to, consciously or unconsciously, want men to be protectors and providers, and frankly so do I. I don’t think women who want that from men are “superficial,” I see it as a legitimate, totally valid need. And focusing on what the man offers and actually does is, truly, less “superficial” than how men size up women, which, until a guy matures, will heavily tilt toward the body. Anyhow, to be useful in that way, protecting, providing, being a doer, taking specific actions, physical or not, that matter to someone, is a core thing in the male psyche (granted, “writing what I know” here does involve projecting forth my own feelings and perspective, but I do think a lot of this is universal across men).

If you don’t believe these male gender roles/attitudes are largely hard-wired, here’s one powerful example from my childhood. When my younger brother and I were little kids, my mom tried to reduce violent toys from our play, no toy guns, bows, arrows, swords, etc; I respect the intention there. But “boys will be boys,” and will play cops and robbers with forefingers as pistols, have light saber duels with paper towel cores, draw great biplane battles (may or may not include King Kong or Godzilla) in school notebooks, and much more. When my brother Jamie was like 5, he put a ball in the exhalation manifold, essentially turning part of his ventilator into A CANNON. That was when mom realized, that kind of thing is deep-seated, irreversible. I’d contend that there’s caveman programming involved, that boys are somehow preparing to guard the women and children in the cave.

There’s socialization to be tough cavemen from infancy on up as well. Author of Raising Boys, Dr. Steve Biddulph, mentions a study that’s shown “parents hug and cuddle girl children far more, even as newborns. And they tend to talk less to boy babies.” This study is discussed in a bit more detail in page 87 of Baby Boys: An Owner’s Manual. I also found evidence in the literature that boy babies tend to toss aside stereotypically girl toys and go for the stereotypically boy stuff, here and here.

Another thing that causes difficulty on the path of the disabled male is that society usually expects men of action to take physical actions (go to place, do thing, go to other place, do another thing, go to work, come back, go to work, etc) not predominately  mental actions (write a story); in this way the modern male gender role can be super restrictive sometimes. This focus on physicality is particularly harsh in high school and college where so many are on the hunt for compatible mates; I feel like even the great author of The Iliad and The Odyssey, Homer, would get the cold shoulder, cut off from the cool cliques like any other disabled guy. A blind, itinerant storyteller like my man H wouldn’t last long in the brutal, unforgiving teen culture. It’d be “run him off like the hobo he is!” High school and college impose an especially painful paradox on guys: during the period that cerebral skills matter most for that man’s future, the cerebral matters least to his peers. Untold numbers of potential geniuses are squashed in the egg this way.

mental actions (write a story); in this way the modern male gender role can be super restrictive sometimes. This focus on physicality is particularly harsh in high school and college where so many are on the hunt for compatible mates; I feel like even the great author of The Iliad and The Odyssey, Homer, would get the cold shoulder, cut off from the cool cliques like any other disabled guy. A blind, itinerant storyteller like my man H wouldn’t last long in the brutal, unforgiving teen culture. It’d be “run him off like the hobo he is!” High school and college impose an especially painful paradox on guys: during the period that cerebral skills matter most for that man’s future, the cerebral matters least to his peers. Untold numbers of potential geniuses are squashed in the egg this way.

Men are not expected to have the physical passivity/motionlessness that my disability entails, society tends to think of that as a stereotypical female trait, and, again, expect men to be men of action. Maybe that goes a long way toward explaining why I’ve been mistaken for female so often in my teens and 20s—almost always by women—including one bizarre incident at an airport when the TSA lady asked my mom if I am supposed to go in the security line for “males or females,” despite the fact I had arrived with heavy 5 o’clock shadow stubble, looking more Bogart than Bacall. I can only speculate that I was mistaken for female because I sit passively still in the wheelchair, lacking masculine body language to signal my boyness. Stuff like that rattled me a little, and definitely left me wondering and feeling like an outsider looking in at normals.

Warren Farrell, who writes books about male psychology, has some interesting insights and ideas on this stuff, that women’s gender roles have changed drastically over the past 50 years while men’s roles remain, he says, fairly unchanged since approximately 1961. This has put “boys and men are decades behind girls and women psychologically and socially, and increasingly behind women academically and economically.” At the high school I went to, boys were most often academic losers, and boys’ attendance at the college I went to has fallen from 60% and 50% male incoming classes 20 years ago to 25% or less today, reflecting a global trend in enrollment in liberal arts colleges. Guys don’t know what path they’re to follow anymore. And I can’t really blame them, given they’re in a society that increasingly frowns on young boys sword-fighting with paper towel rolls or playing index finger pistoleer, in one 2010 case, a Michigan elementary school even suspended a boy for excessive forefinger fire, but still needs them to be soldiers when they grow up. While crackdowns on such “violence” in the public schools continue, this same America simultaneously expects teens to kill and be killed with real violence and real firearms in our unending foreign wars. “He had heard the clinking of the grenade, but he was disoriented after being shot,” says this recent riveting narrative in Stars and Stripes about shredded flesh, blood and survival from Afghanistan.

Dr. Farrell suggests more flexible male gender roles for the 21st century. I hope he’s right and that such shifts prove doable, because as the years go by, it seems headlines about the “boys’ crisis” the U.S. and Canada is experiencing were onto something.

As for disabled men and boys, I feel like a lot of us won’t have much of a chance. Too often, the path of the disabled male is so difficult and the expectations they face—and the expectations they place on themselves, remember, a lot of it is hard-wired—so harsh that they give up; the percentage of men with severe disabilities (on ventilators, etc.) who have already given up is probably fairly astronomical based on what I have observed over the years. Giving up too often seems the only option if there’s no care to even get you out of bed because of malevolent budget cuts against Medicaid services, lack of access to work or social opportunities, even lack of a wooden plank ramp to literally get you in the doors of your community; in short, the ubiquitous barriers in an ableist society. A disabled man who has given up, and spends his life playing video games while his loved ones work to support him may feel like a useless gelding, and that humiliation can become a self-reinforcing loop of pain, the tender masculine heart eventually in lockdown mode; “why bother, I’ll never produce anything of worth.” “I’m not needed anyway.” “I can’t do anything.” To be useless is to not be a good man, and to not be a good man is not to be a person, and to be subhuman means existential terror.

Neither men nor women deserve humiliation. Men are sensitive to words just as much as any human, and if people can avoid the kind of “castrating” language discussed in this—brief and simplistic but surprisingly on target—YouTube video by relationships author “Kara Oh,” then great, all the better to avoid hurting each other. Guys are fairly simple, I think, just wanting to matter and be a valued shiny knight, at root. If a guy is stuck in a self-reinforcing loop of pain and humiliation already, thus already has storms within, and then someone he trusts adds insults on top of it, that’s like adding a hurricane to a hurricane, the perfect storm. It can deepen that humiliation spiral until the male psyche breaks down like an old car.

To conclude, the path of the disabled male means running the gauntlet of ablism, societal expectations, your own expectations, on and on, day-in and day-out. My own desire to have some sort of valuable role as protector or provider or something useful continues. I’ve tried to put out that fire; after all, how’s a mostly bedbound guy on a ventilator gonna assume any sort of role that would be recognizable as a male gender role anyway? But that fire won’t go out, and it’s part of what keeps me doing things, keeps me from giving up. Sometimes I feel that giving up trap‘s gravitational influence tugging on me, and I have to lean against that. I don’t want to get into that spiral. Though I’ve had my down weeks and months, and times of inactivity—especially when hit with recurring illnesses—but not just due to illness, I admit to down times purely due to ineptitude, depression and/or confusion over what to do next.

Where do I fit in? How can I be the protector and provider I want to be in this messed up world? I didn’t have much male guidance growing up, especially after becoming dependent on a BiPap in 1992 and a trach and ventilator in 1994, which more or less made me “a shut-in” for the better part of a decade, and I was a very inquisitive youngster, so I have asked “where do I fit in as a man?” since I was a young teen. I’m 30 now, and realize the only path to resolve that is to forge ahead and find your own answers. I DO NOT want to be a victim, that crap gets old quick. I’d like to feel useful in any role I can carve out, regardless of what anyone expects or thinks; if I can somehow offer worthwhile contributions, give back to my partner/wife and loved ones, I have succeeded.

A controversial essay wasn’t my aim here; my purpose was to shine some light on the lived experience of the path of the disabled man a bit, acknowledging that this barely begins to scratch the tip of the iceberg on this topic; human societies and the people in them are fully immersed in sexuality, gender roles and their expectations, and sex differences, from womb to tomb. If even one person got some new insights, some illumination into life as a man with a disability, great. If one person who loves a man learns a little more about the storms inside the masculine heart, and reaches a bit more harmony with him, all the better. Discord between the yin and yang destroys worlds, while harmony heals them.

May we all find harmony,

Nick