In an incidental comment in a previous blog post, I wrote:

Personally, I think the novel is best used when your/my/the author’s ideas about something large (our past, our future, technology, childhood, humanity, the soul, big stuff) are deep enough that you need an entire novel to explore them in proper detail. Length of a given novel should be tied to exploring its theme, I guess I’m saying…

I thought theme deserved a post of its own. I think that it’s crucial, and understanding theme important, but too often overlooked.

In Philip K Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? the theme is empathy, or …answering how humans are different from androids, what makes us human, which, in the novel, largely boils down to empathy.

Rick Deckard is one of two android-bounty hunters employed by the San Francisco Police Dept., but when the senior bounty hunter gets injured—damn-near killed—by the new androids with the uber-sophisticated Nexus Six brain types, Rick suddenly has the Nexus Six assignment on his desk. The SFPD wants all him to “retire,” deactivate, kill, these loose Nexus Sixes, and since they’ve proven so

dangerous, they want the mission done within 24 hours. This complex and super tough assignment falling to Rick is the inciting incident.

Hunting down the “andys” is more difficult than ever, since the difference between humans and the most advanced androids has narrowed so much; they’re physically indistinguishable and psychologically and socially getting harder and harder to tell apart. With the Nexus Six brain types, the only way to identify one as non-human is to either with the Voigt-Kampff test—measuring empathetic responses in increasing facial blood flow, or lack thereof, when asked a series of questions—or the simpler Boneli Test, which measures reaction time to visual stimuli, as it’s a fraction of a second slower in androids. Rick only knows the Voigt-Kampff test, meaning he has to put facial electrode pick-ups on andys and interview them before killing them, excepting active combat situations, when a post-mortem bone marrow microscopy test is used to confirm inorganic status.

It’s possible for the Nexus Sixes to appear indistinguishable from humans with psychopathic tendencies or stunted or low empathy on the Voigt-Kampff test. It’s implied that the upcoming Nexus-7 brain types, expected to be released in a matter of months, will be able to pass the Voigt-Kampff test and the Boneli test.

The questions on the Voigt-Kampff test stem from the culture and dominant philosophy/religion of post-apocalyptic humanity, Mercerism. Humanity has mostly left for the Mars colonies, since Earth’s an irradiated, desert hellscape following the nuclear devastation of World War Terminus. The government incentivizes emigration with free android helpers for Mars colonists, but enforces an android ban on Earth, where few people remain aside from those whose jobs require it (like Rick) and the population who’ve been affected by the radiation badly enough it has lowered their working-skills or I.Q., and are officially regarded as mutated subhumans, and therefore banned from emigrating by the government; unofficially they’re called the derogatory name “chickenheads.”

Mercerism has apparently grown up in response to the android dystopia and fallout-induced extinction of most Earth animals, and is built around the importance of empathic connections with humans and animals. So questions on the Voigt-Kampff test take for granted that Mercerism is everyone’s belief, assuming strong empathic connections with animals, and asking things to elicit horror and disgust around eating, killing animals, fur rugs, etc.

With most animals extinct, remaining animals are highly prized, and owning an animal (very expensive) a major badge of honor and status symbol. Men having a midlife crisis buy a goat or something, not a car, since animals are rare and flying cars ubiquitous. Mercerism has made people more human, or at least people have focused on the human characteristics that android duplicates can’t mimic or understand, empathic connection with animals and the main ceremony of Mercerism, the empathy box, which is sort of a virtual world that lets the people connect with the prophet Wilbur Mercer and feel his pain as he’s pounded with rocks.

Mercerism and the valuing of having an animal at home to empathize with, those are my favorite parts of the novel. There’s kind of a keeping up with the Jones competition around owning an animal… “I own a goat,” “well, I own a mare, and she’ll make more horses,” but it’s a competition to restore species. The demand for animals is so great, some get electric animals, as they’re less expensive, or perhaps duplicates of species that are legitimately extinct (like owls and most other avian species). Rick Deckard finds his electric sheep deeply depressing, though.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is theme driven, more theme driven than any other example I can think of… because the theme question, “how are we different from identical-brained androids?” drives the plot. In order to hunt down the andys on his list, Rick Deckard has to understand the difference and is haunted by the similarities, so his search, the plot, is all wrapped up in the theme. If the human brain can be duplicated with exactitude, synapse by synapse, which (by the way) IBM’s Blue Brain Project is working toward and is already seeing progress with, how would we humans be different from androids with those identical brains and flesh and bone that’s indistinguishable until put under a microscope? (the Battlestar Galactica reboot’s cylon duplicates seem to be inspired by Philip K. Dick’s androids in this book)

Assuming an identical-brained android, humans are different in their having a soul and the capacity for empathic connection, these are things that can’t be duplicated. And all this zeroing-in on what makes us human is done through showing, not telling.

While Rick Deckard struggles with the lines between android and human, J.R. Isadore, the novel’s other protagonist, a “chickenhead” who empathizes with andys and animals (electric and otherwise), in fact he can’t always tell them apart in his job picking up electric animals as a driver for an electric “animal hospital,” is hoping for connection in his abandoned neighborhood. J.R. Isadore is clearly the most autobiographical character here—Philip K. Dick used J.R. Isadore as a pen name a few times—and his empathy and generosity, almost like his mental disabilities also deteriorate the logical walls most people have to divide up empathy, is poignant and beautiful. He empathizes with the androids, and the most terrifying scene is one where this female andy, incapable of empathy but super-intelligent and manipulative, something close to a high-functioning human psychopath (moreso than the other andys), begins to dismember a spider, perhaps the last spider on Earth. J.R. empathizes with the spider, empathizes with the andys (and they outnumber him 3-to-1) and there’s nothing he can do; we feel his conflicted agony as this horrible female disrespects and maims a life-form she doesn’t understand or appreciate in the slightest.

Having J.R. Isadore there illuminating other facets of the theme takes Do Androids Dream from great sci-fi novel to great literature that adds to our humanity. It works so well because its theme neatly drives the tightly-structured plot, which covers an incredible amount of ground in just over 61,000 words. It is extremely organized storytelling, ironic coming from an author known for stream of consciousness narratives and, literally, being schizophrenic.

This book has so much humanity in it: there’s something really beautiful about how the gentle J.R. Isadore and violent Rick Deckard alike want animals to love and connect with… both feel this terrible yearning for extinct species to return, that the human race is incomplete without all Earth’s animals. They are part of our Earth family.

The version of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? I had (from the New York Public Library online MP3 audiobook collection) was packaged as Blade Runner, the name of the 1982 movie (actually taken from the title of an Alan E. Nourse novel), a new audiobook version released in 2007 by Random House Audio to coincide with the release of Blade Runner: The Final Cut. But this audiobook, read by Scott Brick, has the same content as Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Blade Runner

I rate it a must-read, a classic.

Theme, well-written, can be the difference between good, great and classic.

What’s the theme of George R. R. Martin’s novel A Game of Thrones? (the first book in his A Song of Ice and Fire series)

I don’t know what the theme is… perhaps you’d have to read more books in the Song of Ice and Fire series before a clear theme emerges. The first book is roughly 284,000 words long, and though all of the words seem needed for all the complex, viewpoint-characters—chapter-breaks mean a different character’s point of view, telling the story from multiple viewpoints—I started having difficulties with book two, A Clash of Kings, which weighs-in at a daunting 326,000 words (approximately). It’s clear why it takes Martin five years or so to complete each novel in this series: they’re hefty behemoths. I got bogged-down in A Clash of Kings because of the length, the fact that characters from the background in book one (that we’ve not had time to really know and invest in) are given chapters to helm the viewpoint, even total a-hole Theon Greyjoy. And an obvious theme to buy-into is not readily available.

The theme is probably like this George R.R. Martin quote that’s been going around Twitter: “History is a wheel, for the nature of man is fundamentally unchanging.” It reflects a bleaker worldview than Philip K. Dick’s novel with killing eerily-human robots on a devastated, irradiated, dead Earth ^

But A Song of Ice and Fire isn’t bleak really, because the theme—even assuming it is discernible and I described it remotely accurately—isn’t prominent in the novels. Martin foregrounds character more than anything else. A Song of Ice and Fire is character-driven, as is typical of epic fantasy, and it works so well (and nearly sells more copies than the rest of the fantasy genre combined) because of

its awesome, iconic characters, his uncommonly vivid characterizations and rich story-arcs for viewpoint-characters that draw you in like no one else’s characters.

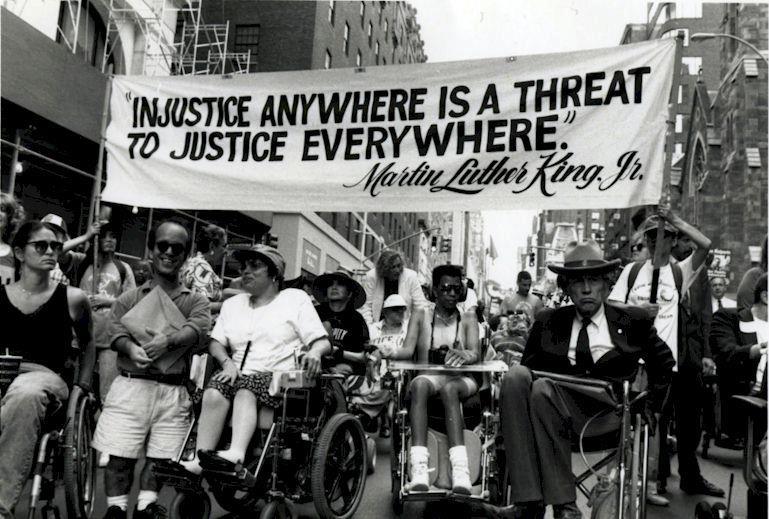

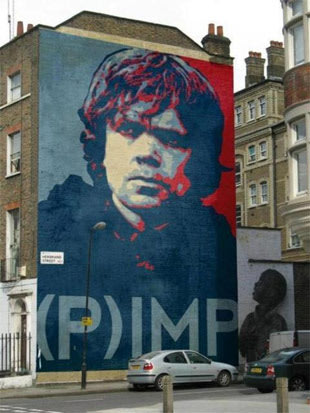

Richly-complex, iconic characters like Daenerys, Mother of Dragons™, Tyrion the Imp™ and Jaime the Kingslayer™ drive the story and are hard not to follow and root for, even when richly-layered with past misdeeds and evil-doings, and that’s why they translate so well to the screen (and to hilarious internet memes). Thanks to the HBO series, Martin’s characters have become pop culture giants. Tyrion (as portrayed by Peter Dinklage) has become a disability icon of sorts, making what’s obvious in the disability community—that the physically “other” are no less protagonists (or villains) than anyone else, even amidst medieval civil wars—mainstream.

I grok that many novels won’t have a theme, and it’s okay to mainly focus on character and/or plot; not everything has to explore deeper issues,

Still, I love a good theme.

Nick